And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts

— William Wordsworth

This is a personal post about beauty and grief, about growth and art, about nature and social connection.

I.

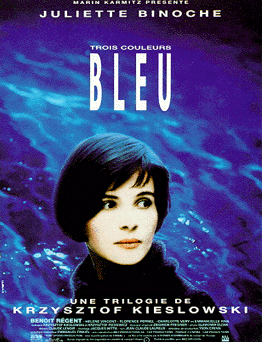

I begin with one of my favorite films, Trois Coleurs: Bleu, directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski and starring Juliette Binoche. In it, Binoche’s character, Julie, loses her husband and daughter in a car crash, initiating a grieving process that unfolds throughout the film. Part of a trilogy in which each film represents one color and theme of the French flag, Bleu’s explicit central theme is liberty (the other colors of the flag, White (equality), and Red (fraternity), make up the rest of the trilogy).

As Julie navigates the pain of loss, and the ways that it cuts across her family, home, and professional worlds, she seems to pursue a dysfunctional version of liberty, she doesn’t want freedom to pursue a desirable goal, but rather freedom from all of her worlds. She moves out of her home, cuts off all of her social ties, destroys her professional work (or at least tries to), and pursues a solitary life in a small flat.

None of these efforts to cut out her past is enough, though: mid-film she goes further, declaring that she wants to be free from memory itself. She expresses this desire to her mother, who is in a home with dementia and does not recognize Julie as her own daughter. The room they stand in is a sad space of glass, mirrors, and a TV screen filled with meaningless images, visually representing the emptiness of her mother’s consciousness. Julie’s wish to have no memory, juxtaposed against the half-life of someone for whom that is the case, reveals to viewers just how self-destructive her wish is–a willful cognitive amputation as “liberty.”

II.

I watch Bleu every 5-10 years, and since the last time I’ve watched it, in my own ways I also have experienced some of the losses that Julie has, including losing parents to dementia. What I discovered when I watched it after my own experiences of grief was that I had feelings toward the characters, and saw details in the film, that I never had had or had seen before. Before I had understood Julie’s emotional frigidity, her unhealthy disconnection from her friends, her rejection of her work–all as symptoms of her grief, which they clearly are. But my understanding of grief was merely conceptual, and not experiential, and so her symptoms to me were all art elements–aesthetic signs arranged skillfully to create a picture of grief. I admired Kieślowski’s artistic representation of them, much as I did the cinematography or the brilliant soundtrack.

In contrast, in my recent viewing they were no longer merely art elements; they were points of connection, or recognition, of tender empathy. No longer did I, as a viewer, mentally hurry Julie to pull herself together and heal. I focused on, rather, her false starts. For example, throughout the film are cuts of her swimming in a darkly lit pool, alone. In Western art, images of water are strongly associated with baptism and rebirth, so one might expect Kieślowski to use such an image to indicate her recovery. Except on this viewing, I realized that the swimming scene is shown time and again, almost like punctuation between scenes. All of these efforts after rebirth are failed baptisms. I recognized them, those sacred missteps, and I silently encouraged her to take her time with them.

Reflecting on this recent viewing, I realized that I could no longer watch Bleu as I had done so many times before. What I had most appreciated about the film, including its subtle composition and breathtaking formalism, seemed to miss the point. Yet what that point was, and what I had gained in return, I struggled to understand.

III.

Last night, I read William Wordsworth’s “Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey on Revisiting the Banks of the Wye During a Tour.” Memory is a central concept in that poem as well, because in it, a poet revisits a natural setting he had visited five years prior, and, among other things, he compares the two experiences. As I read it I thought about my two most recent viewings of Bleu, also separated by about five years.

In “Tintern Abbey,” Wordsworth’s poet describes the transformative experience of the earlier visit:

For nature then [...] To me was all in all. --I cannot paint What then I was. The sounding cataract Haunted me like a passion: the tall rock, The mountain, and the deep and gloomy wood, Their colors and their forms, were then to me An appetite; a feeling and a love

His feelings–much like those of my earlier viewings of Bleu–are unmediated responses to a transcendent encounter. It is as though the object of beauty–a scene from nature in his case, an art film in mine–simply overwhelm us (“I cannot paint / What then I was”), and we each reveled in the transcendent beauty outside of us.

Upon his return five years later, though, Wordsworth has an entirely different experience.

That time has passed. [...] For I have learned To look on nature, not as in the hour Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes The still, sad music of humanity, [...] And I have felt A presence that disturbs me with the joy Of elevated thoughts: a sense sublime Of something far more deeply interfused, [...] A motion and a spirit, that impels All thinking things, all objects of all thought, And rolls through all things. Therefore I am still A lover of the meadows and the woods, And mountains

Wordsworth has lost something: the “aching joys” and “dizzy raptures” of his initial experience. But he also believes that he receives “abundant recompense” in return. The second visit to the scene entails a joining–at once rapturous and melancholic–of the sacred nature scene, and two moments of his consciousness, in which the earlier moment (five years earlier) is expanded by the encounter with nature, and the later moment (in the present) is that expanded consciousness in dialogue with nature, a consciousness that contains both the “still, sad music of humanity” and “a [love] of the meadows and woods.”

IV.

Reflecting on the parallels between myself and Wordsworth’s poet, and the criss-crossing themes of memory, beauty, and loss, I started to piece together what I was striving for on my recent viewing of Bleu.

One of Kieślowski’s artistic achievements in the trilogy is to show how ideals–liberty, equality, and fraternity–are all double-edged. Each is presented and developed in a dark and ironic way, and yet each is eventually redeemed as well. Throughout most of Bleu, Julie’s pursuit of liberty, and the ways she seems to experience it when she grasps it, are demented; grief is/as dementia. But as Julie re-enters the social world, she discovers that there is liberty also in interdependence. Ideals, not just people, can fall and can be redeemed; likewise, emotional pain is in time redemptive.

Correspondingly, one of Wordsworth’s achievements is to help us appreciate the difference between immature responses to the beautiful, characterized by an almost cause-effect aesthetic ecstasy, and mature ones, where we bring our full and expanded selves into the encounter and give it everything we’ve got, such that the “mighty world” that is revealed in the encounter is not just given to us, but rather is half-created by us. For Wordsworth, when inhabiting that “mighty world,” he becomes “a living soul,” and he feels the “deep power of joy” through which “We see the life of things.” Notably, Wordsworth ends the poem not with poetic abstractions, but with a deepened bond with his sister–so like Julie, he experiences a transition from private experience to social interdependence.

My own experiences of life recently contributed a more mature response from me to Kieślowski’s Bleu than I had had before. This recent viewing “disturb[ed] me with the joy of elevated thoughts” (Wordsworth’s insightful integration of disturbance, joy, and elevation in a single phenomenon is cool), and, as I often do, I turned to writing to help me work them out. What I have learned is not so easy to express in propositional language–aesthetic insight seldom is.

But I am learning to see that processes of emotional pain that we might wish to just “get over with,” are in fact formative of our capacity to “see the life of things,” to experience the world with “a sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused.” And I believe that all of this has helped me to be more perceptive about how the complex relationships among freedom, grief, and memory constitute a locus of deepened connections, of recognition and acknowledgment–and a turning outward for me as well: to my reader, to you.